"For the last century, or more, we have been experimenting with the rule of democracy--the bludgeoning by governors whom majorities, drunk with power, impose on vanquished minorities. This last is probably the worst of all, for we stand to-day steeped to the lips in a universal corruption that is rotting every nation to the core. Is it not a fact that, whether it be a French Deputy or an English Member of Parliament, a Republican, a Democratic, or a Socialist candidate for office, each and every one of them sings exactly the same siren song: "Clothe me with power, and I will use it for your good "? It has been the song of every tyrant and despoiler since history began."--W.C. Owen, "Anarchism versus Socialism"

W(illiam) C(harles) Owen (2/16/1854-7/9/1929), individualist-anarchist, author of The Economics of Herbert Spencer, "Anarchism versus Socialism" (and here), "Elisée Reclus", "England Monopolised or England Free?", "Full steam astern! Is this progress or the road to ruin?", "The Mexican revolution, its progress, causes purpose and probable results" and numerous other essays was born in Dinapore, India, raised in England, and emigrated to the United States in 1882.

His socialist leanings led him to become a member of the International Workingmen's Association in California. He discovered Kropotkin's writings and translated of several of his works, beginning his travel from socialism to anarchism. He was a contributor to Burnette G. Haskell's (1857-1907) San Francisco Truth (1882-97); editor of Nationalist of Los Angeles (1890) and San Francisco (1891-4); and contributed to Commonweal, organ of the Socialist League (which had been taken over by anarchists in 1890) of William Morris in England. In 1890, in New York, with Italian Saverio Merlino he joined the league and became a founder of the New York Socialist League in 1890. He was expelled from the League in 1892. Owen, now influenced by Benjamin Tucker, became an anarchist-individualist. He contributed to Freedom from 1893 on and returned to California to work as a journalist, where he would become involved in the land question, a subject which he would turn to again and again. Owen also contributed to the libertarian weekly "Free Society" in San Francisco (1897-1904) and Emma Goldman's "Mother Earth".

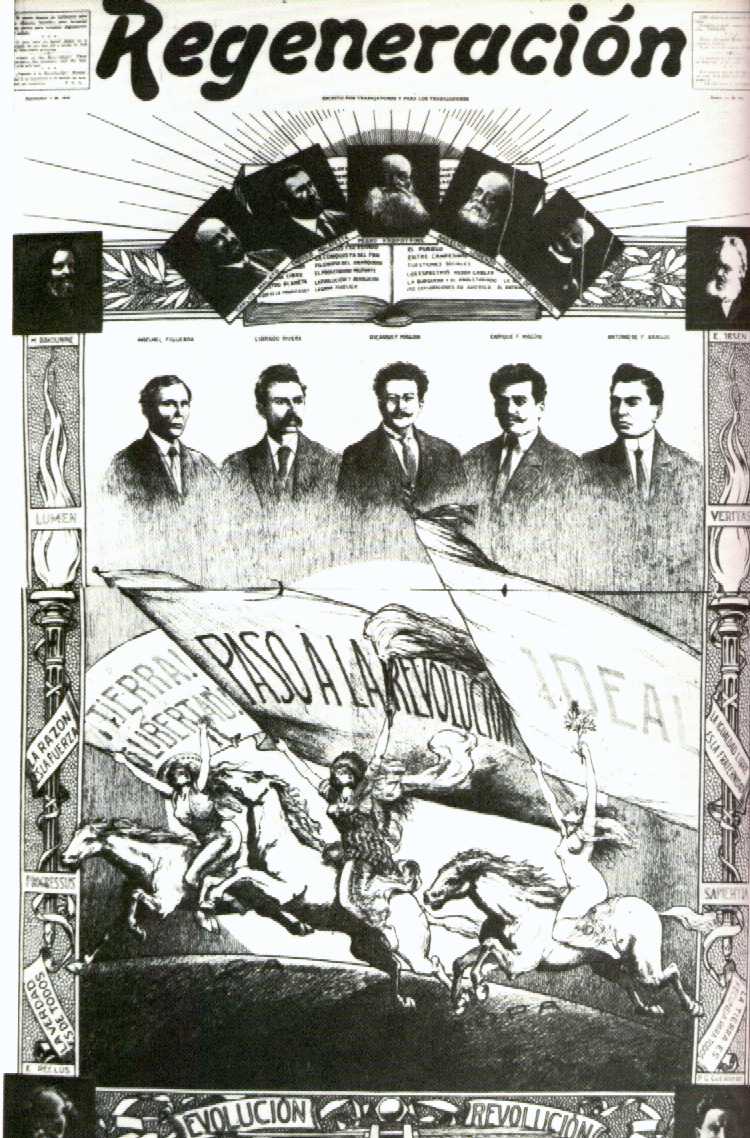

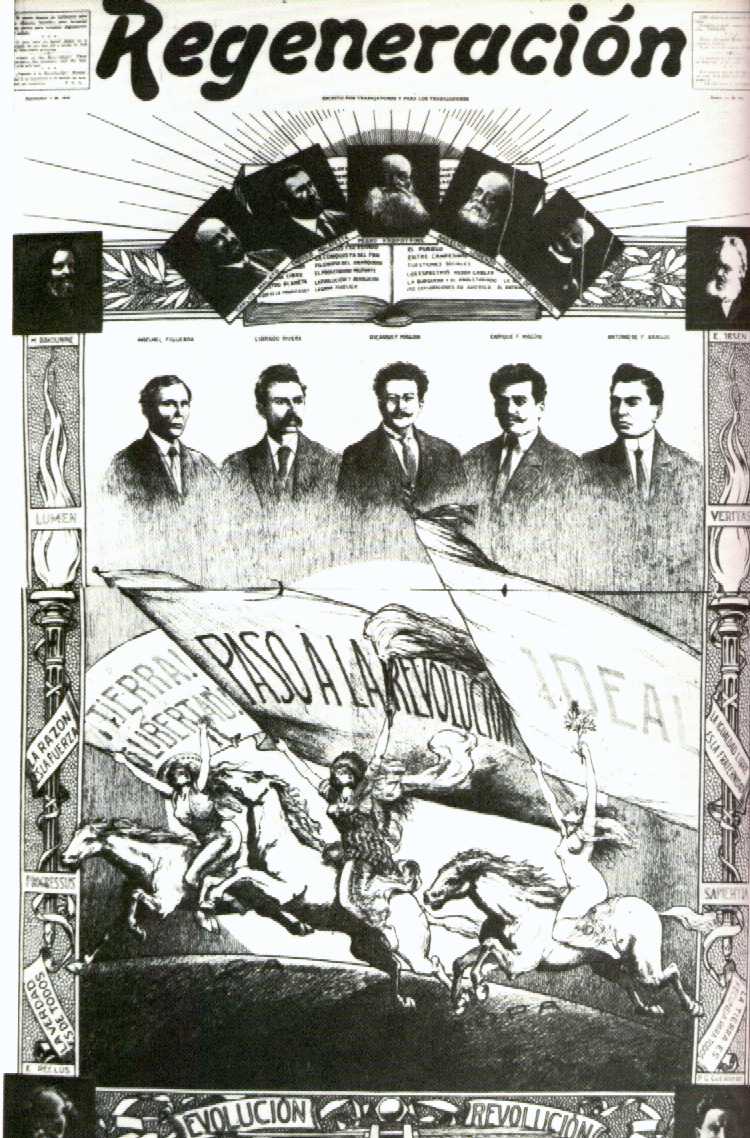

In 1911, he began his work withRicardo Flores Magón (1874-1922) and his brother, Enrique Flores Magón and becomes editor of the English section of Regeneración (1910-1916) and corresponds throughout the international libertarian press. Many anarchists, both individualist and collectivist, throughout the western United States would actively support the Magón brothers and their revolutionary activities in Baja California. Emma Goldman, in her biographical essay, "Voltairine de Cleyre," said, Voltairine

"fervently took up the fight of the Mexican people who threw off their yoke; she wrote, she lectured, she collected funds for the Mexican cause"

before dying in 1912 (in Sharon Presley and Crispin Sartwell's

Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine de Cleyre--Anarchist, Feminist, Genius (Albany, SUNY Press, 2005. p. 38). Their offices and activities were centered in Los Angeles and Tijuana where most of their publications were produced. In the 1970's, I tracked down their address in the center of Los Angeles and kept some pieces of the old brick building which had been torn down. Only the foundation was left.

He published his own periodical, "Land & Liberty" (1914-15) and then in 1916 returned to England (1916). At that time, anarchist immigrants, especially activists, in the United States were under severe pressure from the federal government to be deported and the U.S. Attorney in Los Angeles was seeking

"a federal indictment against [any anarchists involved]...for conspiring to overthrow the government of the United States and to invade Mexico." (William Preston, Jr. Aliens and Dissenters: Federal Suppression of Radicals, 1903-1933 (NY: Harper & Row, 1963, p. 53).

Congressmen were applauded in Congress for saying such things as

"Now I would execute these anarchists if I could, and then I would deport them, so that the soil of our country might not be polluted by their presence even after the breath had gone out of their bodies. I do not care what the time limit is. I want to get rid of them by some route... or by execution by the hangman. It makes no difference to me so that we get rid of them." (ibid., p. 83).

On February 18, 1916, Enrique & Ricardo Flores Magón were arrested at their Community Farm near Los Angeles, California. Enrique was beaten by the police and hospitalized. The Magón brothers were charged with mailing articles inciting "murder, arson and treason," and go on trial May 21. Both were convicted, given prison sentences and fines.

As Owen's friends and fellow-travelers in the I.W.W. poetically said at the time that WWI was beginning,

I love my flag, I do, I do.

Which floats upon the breeze,

I also love my arms and legs,

And neck, and nose and knees.

One little shell might spoil them all

Or give them such a twist,

They would be of no use to me;

I guess I won't enlist.I love my country, yes, I do

I hope her folks do well.

Without our arms, and legs and things,

I think we'd look like hell.

Young men with faces half shot off

Are unfit to be kissed,

I've read in books it spoils their looks,

I guess I won't enlist.

(ibid., p. 89)

When back in London, he took part in the newspaper "Freedom" (1886-?) and the Freedom Press, joined the Commonwealth League, and wrote for its organ Commonweal. In 1926, he became part of a small co-operative colony close to Storrington (Sussex). W.C. Owen died in Worthing, Great Britain in 1929.

Along with Auberon Herbert, Victor Yarros, Henry Bool, Charles T. Sprading and a few other writers, he would be regarded as among the best of the Spencerian Anarchists, integrating the insights of Herbert Spencer with individualist-anarchism. Marcus Graham (aka Shmuel Marcus, 1893-197?, Romanian-born editor of the anarchist journal Man! (1933-40) would say of Owen that

"He proved to be one of the most interesting men I ever had the good fortune to know. We met often and he was a fountain of knowledge in every respect...Owen's spirit was that of a revolutionary...Owen carried on a long correspondence with me until his death, and his reading and correcting the proofs of the Anthology [of Revolutionary Poetry (New York: The Active Press, 1929)] was of immense value." Marcus Graham, MAN! An Anthology of Anarchist Ideas, Essays, Poetry and Commentaries (London: Cienfuegos Press, 1974. p. 10)

Anarchy versus Socialism

Introduction

"Anarchy versus Socialism", W.C. Owen's best-known work, was written originally around 1902 at the request of Owen's friend, Emma Goldman, who wanted a work detailing the difference between Anarchism and Socialism, most likely, as a response to Daniel DeLeon's "Socialism versus Anarchism"(Girard, Kansas: People's Pocket Series No. 5; Appeal to Reason. Lecture Delivered at Boston, October 13, 1901. The individualist-anarchist, A.H. Simpson, was in the audience and provided questions for DeLeon which are valuable to read, just as E. Belfort Bax's "'Voluntaryism' versus 'Socialism'", a response to Auberon Herbert, is useful). It was Owen's belief that no honest alliance was possible between the two. As he said,

"either you believe in the right of the Individual to govern himself, which is the basis of Anarchism, or you believe that he must be governed by others, which is the cornerstone of all those creeds which should be grouped generically as Socialism. One or the other must be the road to human progress. Both cannot be."

The following is a condensed version of his essay:

Man is manifestly destined to be master of himself and his surroundings, individually free. His capacity for achievement has shown itself practically boundless, whenever and wherever it has been permitted the opportunity of expansion; and no less an ideal than equal and unfettered opportunity--that is to say, individual freedom--should satisfy him...[A]ll forms of slavery [are] a refusal to recognize Man's dignity or native worth.

Anarchism

[S]o long as the ordinary individual remains unconscious of his proper dignity as the great thinking animal, slavery, in my judgment, will continue. The first essential business, therefore, is to awaken thought; to get men to look at things as they are; to induce them to hunt for truth.

To us the problem is not merely economic...[T]he promotion of individuality, and the encouragement of the spirit of revolt against whatever institutions may be unworthy of humanity, are everything. We are rebels against slavery, and we understand that men will win their way to freedom only when they yearn to be free.

Back of all this infamy stands always the Government machine; dead to all human sympathy, as are all machines; bent only on increasing its efficiency as a machine, and enlarging its power; organized expressly to keep things, in all essentials, precisely as they are. It is the arch-type of immobility, and, therefore, the foe of growth. It is the quintessence of compulsion, and, therefore, the enemy of freedom. To it the individual is a subject, of whom it demands unquestioning obedience. Necessarily we Anarchists are opposed to it. We do not dream, as do the Socialists, of making it the one great Monopolist, and therefore the sole arbiter of life. On the contrary, we seek to whittle away its powers, that it may be reduced to nothingness and be succeeded by a society of free individuals, equipped with equal opportunities and arranging their own affairs by mutual agreement.

[Echoing Herbert Spencer, [t]he Anarchist type of social structure is the industrial type, and for it the true industrialist, the working man, should stand. On the other hand, he who cries for more Government is declaring himself an advocate of the military type, wherein society is graded into classes and all life's business conducted by inferiors obeying orders issued by the superior command. That offers the worker only permanent inferiority and enslavement, and against that he should revolt.

[T]he State...deprives men of personal responsibility, robs them of their natural virility, takes out of their hands the conduct of their own lives, thereby reduces them to helplessness, and thus insures the final collapse of the whole social structure.

[Anarchism i]s based on the conception that the Individual is the natural fount of all activity, and that his claim to free and full development of all his powers is paramount. The Socialist interpretation, on the other hand, is presented as resting on the conception that the claim of the Collectivity is paramount, and that to its welfare, real or imagined, the Individual must and should subordinate himself.

On the correct interpretation of Life everything depends, and the question is as to which of these two conflicting interpretations is correct. Always and everywhere the entire social struggle hinges on that very point, and every one of us has his feet set, however unconsciously, in one or other of these camps. Some would sacrifice the Individual, and all minorities, to the supposed interests of the collective whole. Others are equally convinced that a wrong inflicted on one member poisons the whole body, and that only when it renders full justice to the Individual will society be once more on the road to health.

[T]he existing system is a miserable compromise between Anarchism and Socialism with which neither can be content. On the one hand, the Individual is instructed to play for his own hand, however fatally the cards are stacked against him. On the other hand, he is adjured incessantly to sacrifice himself to the common weal. Special Privilege, when undisturbed, preaches always individual struggle, although it is Special Privilege that robs the ordinary individual of all his chances of success. Let Special Privilege be attacked, however, and it appeals forthwith to the Socialistic principle declaring vehemently that the general interests of society must be protected at any cost.

When a man says he is an Anarchist he puts on himself the most definite of labels. He announces that he is a "no rule" man. "Anarchy"--compounded of the Greek words "ana," without, and "arche," rule--gives in a nutshell the whole of his philosophy. His one conviction is that men must be free; that they must own themselves.

Anarchists do not propose to invade the individual rights of others, but they propose to resist, and do resist, to the best of their ability all invasion by others. To order your own life, as a responsible individual, without invading the lives of others, is freedom; to invade and attempt to rule the lives of others is to constitute yourself an enslaver; to submit to invasion and rule imposed on you against your own will and judgment is to write yourself down a slave.

Anarchism stands for the free, unrestricted development of each individual; for the giving to each equal opportunity of controlling and developing his own particular life. It insists on equal opportunity of development for all, regardless of colour, race, or class; on equal rights to whatever shall be found necessary to the proper maintenance and development of individual life; on a "square deal" for every human being, in the most literal sense of the term.

Moreover, it matters not to the Anarchist whether the rule imposed on him is benevolent or malicious. In either case it is an equal trespass on his right to govern his own life. In either case the imposed rule tends to weaken him, and he recognizes that to be weak is to court oppression.

So, from the exact Greek language the precise and unmistakable word "Anarchy" was coined, as expressing beyond question the basic conviction that all rule of man by man is slavery.

The entire Anarchist movement is based on an unshakeable conviction that the time has come for men--not merely in the mass, but individually--to assert themselves and insist on the right to manage their own affairs without external interference; to insist on equal opportunities for self-development; to insist on a "square deal," unhampered by the intervention of self-asserted superiors.

[U]nder the artificial conditions imposed on them by rulers, who portion out among themselves the means of life, millions of the powerful species known as "Man" are reduced to conditions of abject helplessness of which a starving timber-wolf would be ashamed. It is unspeakably disgusting to us, this helplessness of countless millions of our fellow creatures; we trace it directly to stupid, unnatural laws, by which the few plunder and rule over the many, and we propose to do our part in restoring to the race its natural strength, by abolishing the conditions that render it at present so pitiably weak.

For the last century, or more, we have been experimenting with the rule of democracy--the bludgeoning by governors whom majorities, drunk with power, impose on vanquished minorities. This last is probably the worst of all, for we stand to-day steeped to the lips in a universal corruption that is rotting every nation to the core. Is it not a fact that, whether it be a French Deputy or an English Member of Parliament, a Republican, a Democratic, or a Socialist candidate for office, each and every one of them sings exactly the same siren song: "Clothe me with power, and I will use it for your good "? It has been the song of every tyrant and despoiler since history began.

It is you yourselves, governed by the misrepresentations of superstition, and not daring to lift your heads and look life in the face, who substitute for that magnificent justice the hideously unjust inequalities with which society is sick well-nigh to death. Does not the experience of your daily life teach you that when, in any community, any one man is loaded with power it is always at the expense of many others, who are thereby rendered helpless?

Let us not flatter ourselves that we can shirk this imperative call to self-assertion by appointing deputies to perform the task that properly belongs to us alone. Already it is clear to all who look facts in the face that the entire representative system, to which the workers so fatuously looked for deliverance, has resulted in a concentration of political power such as is almost without parallel in history.

Our representative system is farce incarnate. We take a number of men who have been making their living by some one pursuit--in most cases that of the law--and know nothing outside that pursuit, and we require them to legislate on the ten thousand and one problems to which a highly diversified and intricate industrial development has given rise. The net result is work for lawyers and places for office-holders, together with special privileges for shrewd financiers, who know well how to get clauses inserted in measures that seem innocence itself but are always fatal to the people's rights.

Anarchism concentrates its attention on the individual, considering that only when absolute justice is done to him or her will it be possible to have a healthy and happy society. For society is merely the ordinary citizen multiplied indefinitely, and as long as the individuals of which it is composed are treated unjustly, it is impossible for the body at large to be healthy and happy. Anarchism, therefore, cannot tolerate the sacrifice of the individual to the supposed interests of the majority, or to any of those high-sounding catchwords (patriotism, the public welfare, and so forth) for the sake of which the individual--and always the weakest individual, the poor, helpless working man and woman--is murdered and mutilated to-day, as he has been for untold ages past.

Only by a direct attack on monopoly and special privilege; only by a courageous and unswerving insistence on the rights of the individual, whoever he may be; on his individual right to equality of opportunity, to an absolutely square deal, to a full and equal seat at the table of life, can this great social problem, with which the whole world now groans in agony, be solved.

In a word, the freedom of the individual, won by the abolition of special privileges and the securing to all of equal opportunities, is the gateway through which we must pass to the higher civilisation that is already calling loudly to us.

It is urged that we Anarchists have no plans; that we do not set out in detail how the society of the future is to be run. This is true. We are not inclined to waste our breath in guesses about things we cannot know. We are not in the business of putting humanity in irons. We are trying to get humanity to shake off its irons. We have no co-operative commonwealth, cut and dried, to impose on the generations yet unborn. We are living men and women, concerned with the living present, and we recognize that the future will be as the men and women of the future make it, which in its turn will depend on themselves and the conditions in which they find themselves. If we bequeath to them freedom they will be able to conduct their lives freely.

To overthrow human slavery, which is always the enslavement of individuals, is Anarchism's one and only task. It is not interested in making men better under slavery, because it considers that impossible--a statement before which the ordinary reader probably will stand aghast. It seems, therefore, necessary to remind him once again that Anarchists are realists who try to see Life as it is, here on this earth, the only place where we can study it, indeed the only place whereon, so far as hitherto discovered, human life exists. Our view is that of the biologist. We take Man as we find him, individually and as a member of a species. We see him subject to certain natural laws, obedience to which brings healthy growth while disobedience entails decay and untimely death. This to us is fundamental, and much of Anarchism's finest literature is devoted to it.

Now, from the biological standpoint, Freedom is the all-essential thing. Without it individual health and growth are impossible... Biologically we are all parts of one organic whole--the human species--and, from the purely scientific standpoint, an injury to one is the concern of all. You cannot have slavery at one end of the chain and freedom at the other. In our view, therefore, Special Privilege in every shape and form, must go. It is a denial of the organic unity of mankind; of that oneness of the human family which is, to us, a scientific truth. ...Internationalism is, to us, a biological fact a natural law which cannot be violated with impunity or explained away. The most criminal violators of that natural law are modern Governments, which devote all the force at their command to the maintenance of Special Privilege, and, in their lust for supremacy, keep nations perpetually at war. Back of all this brutal murdering is the thought: "Our governing machine will become more powerful. Eventually we shall emerge from the struggle as rulers of the earth."

This earth is not to be ruled by the few. It is or the free and equal enjoyment of every member of the human race. It is not to be held in fee by old and decaying aristocracies, or bought up as a private preserve by the newly rich--that hard-faced and harder-conscienced mob which hangs like a vulture over every battlefield and gorges on the slain...For, just as the human species is one organic whole, so the earth, this solid globe beneath our feet, is one economic organism, one single store-house of natural wealth, one single workroom in which all men and women have an equal right to labour.

To every Anarchist the right to free and equal use of natural opportunities is an individual right, conferred by Nature and imposed by Life. It is a fundamental law of human existence.

It is a question of intelligence, and to Anarchists the methods generally proposed for restoring the land to the use of the living do not appear intelligent. Clearly Nationalization will not do; for Nationalization ignores the organic unity of the human species, and merely substitutes for monopoly by the individual monopoly by that artificial creation, the State, as representing that equally artificial creation, the Nation. Such a philosophy lands us at once in absurdities so obvious that their bare statement suffices to explode them.

Even Capitalism knows better than that. In theory, as in practice, Capitalism is international, for it recognizes that what is needed by the world at large must pass into the channels of international trade and be distributed.

To all Anarchists, therefore, the abolition of Land Monopoly is fundamental. Land Monopoly is the denial of Life's basic law, whether regarded from the standpoint of the individual or of the species.

In some way or another the Individual must assert and maintain his free and equal right to life, which means his free and equal right to the use of that without which life is impossible, our common Mother, Earth. And it is to the incalculable advantage of society, the whole, to secure to each of its units that inalienable right; to release the vast accumulations of constructive energy now lying idle and enslaved; to say to every willing worker--"Wherever there is an unused opportunity which you can turn to account you are free to use it. We do not bound you. We do not limit you. This earth is yours individually as it is ours racially, and the essential meaning of our conquest of the seas, of air and space, is that you are free to come and go whither you will upon this planet, which is at once our individual and racial home."

The Land Question, viewed biologically, reveals wide horizons and opens doors already half ajar. Placed on the basis of equal human rights, it is nobly destructive, for it spells death to wrongs now hurling civilisation to its ruin. Were free and equal use of natural opportunities accepted as a fundamental law--just as most of us accept, in theory, the Golden Rule--there would be no more territory-grabbing wars. ...Free exchange, so essential to international prosperity, would follow automatically, and with it we should shake off those monstrous bureaucracies now crushing us.

These doors already are standing more than half ajar... Science, annihilating distance, has made, potentially at least, the human family one. What sense is there in fencing off countries by protective tariffs when the very purpose of the railway and the steamship, the cable and the wireless station, is to break through those fences?

All intelligent and courageous action along one line of the great struggle for human rights helps thought and action along other lines, and the contest that is certain to come over the land question cannot but clear the field in other directions. It will be seen, for example, that freedom of production will not suffice without freedom of distribution.

If mankind is ever to be master of itself, scientific thought--which deals with realities and bases its conclusions on ascertained facts--must take the place of guess and superstition. To bring the conduct of human life into accord with the ascertained facts of life is, at bottom, the great struggle that is going on in society.

War

[War] has thrown us back into barbarism. For the moment it has afflicted us with Militarism and scourged us with all the tyrannies that military philosophy and tactics approve of and enforce. Necessarily Militarism believes in itself and in that physical violence which is its speciality. Necessarily it sympathies with all those barbarisms of which it is the still-surviving representative, and distrusts those larger views that come with riper growth. How could it be otherwise? By the essence of its being Militarism does not argue; it commands. Its business is not to yield but to conquer, and to keep, at any cost, its conquests. Always, by the fundamental tenets of its creed it will invade; drive the weaker to the wall, enforce submission. He who talks to it of human rights, on the full recognition of which social peace depends, speaks a language it does not and cannot understand. To Militarism he is a dreamer, and, in the words of the great German soldier, Von Moltke, it does not even regard his dream as beautiful.

Every Government is a vast military machine, armed with all the resources of modern science. Every Government is invading ruthlessly the liberties of its own "subjects" and stripping them of elemental rights. Resolved on keeping, at any cost, its existing conquests, every Government treats as an outcast and criminal him who questions its autocracy. Obsessed perpetually by fear, which is the real root of military philosophy, every Government is guarding itself against popular attack; and with Governments, as with all living creatures, there is nothing so unscrupulous as fear. When Government punishes the man who dares to express honestly his honest thought, does it pause to consider that it is killing that spirit of enquiry which is the life of progress, and crushing out of existence the courageous few who are the backbone of the nation? Not at all. Like an arrant coward, it thinks only of its own safety. When, by an elaborate system of registration, passports, inspection of private correspondence, and incessant police espionage, it checks all the comings and goings of individual life, does it give a thought to personal liberty or suffer a single pang at the reflection that it is sinking its country...? Not a bit of it. The machine thinks only of itself; of how it may I increase and fortify its power.

Just as the Court sets the fashions that rule "Society," so the influence of the governmental machine permeates all our economic life. The political helplessness of the individual citizen finds its exact counterpart in the economic helplessness of the masses, reduced to helplessness by the privileges Government confers upon the ruling class, and exploited by that ruling class in exact proportion to their helplessness. Throughout the economic domain "Woe to the Conquered" is the order of the day; and to this barbaric military maxim, which poisons our entire industrial system and brutalizes our whole philosophy of life, we owe it that Plutocracy is gathering into its clutches all the resources of this planet and imposing on the workers everywhere what I myself believe to be the heaviest yoke they have, as yet, been forced to bear.

Anarchists ... regard Militarism as a straitjacket in which modern Industrialism, now struggling violently for expansion, cannot fetch its breath. And everything that smacks of Governmentalism smacks also of Militarism, they being Siamese twins, vultures out of the same egg. The type now advancing to the centre of the stage, and destined to occupy it exclusively, is, as they see it, the industrial type; a type that will give all men equal opportunities, as of human right, and not tolerate the invasion of that right, a type, therefore, that will enable men to regulate their own affairs by mutual agreement and free them from their present slavery to the militant employing class; a type that will release incalculably enormous reservoirs of energy now lying stagnant ... That such is the natural trend of the evolution now in process they do not doubt; but its pace will be determined by the vigour with which we shake off the servile spirit now para lysing us, and by the intelligence with which we get down to the facts that really count. At bottom it is a question of freedom or slavery; of self-mastery or being mastered.

Our faith is in Science, in knowledge, in the infinite possibilities of the human brain, in that indomitable vital force we have hitherto abused so greatly because only now are we beginning to glimpse the splendour of the uses to which it may be brought.

[H]ow can Science discover except through free experiment? How can the mind of Man expand when it is laced in the straitjacket of authority and is forbidden independence? This question answers itself, and the verdict passed by history leaves no room for doubt. Only with the winning from Militarism and Ecclesiasticism of some measure of freedom did Science come to life; and if the world were to pass again into a similar thraldom, that life would fall once more into a stupor from which it could be shaken only by some social upheaval far greater and more bloody than the French Revolution ever began to be. It is not the champions of Freedom who are responsible for violent Revolutions, but those who, in their ignorant insanity, believe they can serve Humanity by putting it in irons and further happiness by fettering Mankind. We may be passing even now into such a thraldom, for Democracy, trained from time immemorial to servility, has not yet learned the worth of Freedom and Plutocracy would only too gladly render all thought and knowledge subservient to its own profit-making schemes.

[T]he seven great Anarchist writers...--Tolstoy, Bakunin, Kropotkin Proudhon, Stirner, Godwin, and Tucker--calls special attention to the fact that, although on innumerable points they differ widely, as against the crippling authoritarianism of all governing machines they stand a solid phalanx. The whole body of Herbert Spencer's teaching, once so influential in this country, moves firmly toward that goal. His test of Civilisation was the extent to which voluntary co-operation has occupied the position previously monopolized by the compelling State, which he regarded as essentially a military institution. Habitually we circulate, as one of our most convincing documents, his treatise on "Man versus the State," and in his "Data of Ethics" he has given us a picture of the future which is Anarchism of the purest type.

Every organism struggles with all the vitality at its command against extinction; and every Government, whatever it may call itself, is an organism composed of human beings. It exists, and can exist, only by compelling other human beings to remain a part of it; by exacting service from them, that is to say, by making them its serfs and slaves. The organism's real basis is human slavery, and it cannot be anything else.

Socialism

[T]he position of Socialism...is to free mankind. The first difficulty, however, lies in the fact that while the word "Anarchy," signifying "without rule," is exceedingly precise, the word "Socialism" is not. Socialism merely means association, and a Socialist is one who believes in associated life and effort. Immediately a thousand questions of the greatest difficulty arise. Obviously there are different ways in which people can associate; some of them delightful, venue quite the reverse. It is delightful to associate yourself, freely and voluntarily, with those to whom you feel attracted by similarity of tastes and pursuits. It is torture to be herded compulsorily among those with whom you have nothing in common. Association with free and equal partners, working for a common end in which all are alike interested, is among the things that make life worth living. On the other hand, the association of men who are compelled by the whip of authority to live together in a prison is about as near hell as it is possible to get.

To be associated in governmentally conducted industries, whether it be as soldier or sailor, as railroad, telegraph, or postal employee, is to become a mere cog in a vast political machine... Under such conditions there would be less freedom than there is even now under the régime of private monopoly; the workers would abdicate all control of their own lives and become a flock of party sheep, rounded up at the will of their political bosses taking what those bosses chose to give them, and, in the end being thankful to be allowed to hold a job on any terms.

Let no one delude himself with the fallacy that governmental institutions under Socialist administration would be shorn of their present objectionable features. They would be precisely what they are to-day. If the workers were to come into possession of the means of production to-morrow, their administration under the most perfect form of universal suffrage--which the United States, for example, has been vainly trying to doctor into decent shape for generations past--would simply result in the creation of a special class of political managers, professing to act for the welfare of the majority. Were they as honest as the day--which it is folly to expect--they could only carry out the dictates of the majority, and those who did not agree slavishly with those dictates would find themselves outcasts. In reality, we should have put a special class of men in absolute control of the most powerful official machine that the world has ever seen, and should have installed a new form of wage-slavery, with the State as master. And the workingman who was ill-used by the State would find it a master a thousand times more difficult to overthrow than the most powerful of private employers.

Socialists declare loudly that the entire capitalistic system is slavery of the most unendurable type, and that landowning, production, and distribution for private profit must be abolished. They preach a class war as the only method by which this can be accomplished, and they proclaim, as fervently as ever did a Mohammedan calling for a holy crusade against the accursed infidel, that he who is not with them is against them. For this truly gigantic undertaking they have adopted a philosophy and pursue means that seem to us childishly inadequate.

To us it is inconceivable that institutions so deeply rooted in the savagery and superstitions of the past can be overthrown except by people who have become saturated to the very marrow of their bones with loathing for such superstition and such savagery. To us the first indispensable step is the creation of profoundly rebellious spirits who will make no truce, no compromise. We recognize that it is worse than useless to waste our breath on effects; that the causes are what we must go for, and that every form of monopoly, every phase of slavery and oppression, has its root in the ambition of the few to rule and fleece, and the sheepish willingness of the many to be ruled and fleeced.

What is the course that the Socialists are pursuing...? In private they will tell you that they are rebels against the existing unnatural disorder as truly as are we Anarchists, but in the actual conduct of their movement they are autocrats, bent on the suppression of all individuality, whipping, drilling, and disciplining their recruits into absolute conformity with the ironclad requirements of the party. They declare themselves occupied with a campaign of education. They are not. In such a contest as this, wherein the lines are drawn so sharply; where on the one side are ranged the natural laws of life, and on the other an insanely artificial system that ignores all the fundamental laws of life, there can be no such thing as compromise; and he who for the sake of getting votes attempts to make black appear white is not an educator but a confidence man. We are aware that there are many confidence men who grow into the belief that theirs is a highly honourable profession, but they are confidence men all the same.

The truth is that the Socialists have become the helpless victims of their own political tactics. We speak correctly of political "campaigns," for politics is warfare. Its object is to get power, by gathering to its side the majority, and reduce the minority to submission. In politics, as in every other branch of war, the entire armoury of spies, treachery, stratagem and deceit of every kind is utilized to gain the one important end--victory in the fight. And it is precisely because our modern democracy is engaged, year in and year out, in this most unscrupulous warfare that the basic and all-essential virtues of truth, honesty, and the spirit of fair play have almost disappeared.

We raise further that if politics could, by any miracle, be purified, it would mean, if possible, a still more detestable consummation, for there would not remain a single individual right that was not helplessly at the mercy of the triumphant majority. It is imperative, and especially for the weaker--those who are now poor and uneducated--that the "inalienable" rights of man be recognized; and that, while he is now "supposed" to be guaranteed absolute right of free speech and assemblage, and the right to think on religious matters as he pleases, in the future he shall be really guaranteed full opportunities of supporting and developing his life--a right that cannot be taken away from him by a dominant party that may have chanced to secure, for the time being, the majority of votes.

This is the rock on which Socialism everlastingly goes to pieces. It mocks at the basic laws of life. It denies, both openly and tacitly, that there are such things as individual rights; and while it asserts that assuredly, as civilized beings the majorities of the future will grant the minority far greater freedom and opportunity than it has at present, it has to admit that all this will be a "grant," a "concession" from those in power. There probably never has been a despot that waded through slaughter to a throne who has not made similar promises.

The way in which a man looks at a subject determines his treatment of it. If he thinks, with the Socialists, that the collectivity is everything and the individual an insignificant cipher, he will fall in willingly with all those movements that profess to be working for the good of the majority, and sacrifice the individual remorselessly for this supposed good. For example: Although he may admit, in theory, as the Socialists generally do, that men should be permitted to govern their own lives, his belief in legislating for the majority, and the scant value he puts on the individual life, will lead him to support such movements as Prohibition, which, in the name of the good of the majority, takes away from the individual, absolutely and in a most important matter--as in the question of what he shall and shall not drink--the command of his own life.

Apparently Socialists cannot conceive of a society run on other than the most strictly centralized principles. This seems to us a profound error.

Locomotion is the industry of all others that seemed, by its very nature, doomed to centralization, yet even in this department the tide of decentralization has set in with extraordinary rapidity. With the advent of the bicycle came the first break the individual machine becoming at once a formidable competitor of the street car companies. The tendency received a further and enormous impetus with the introduction of the motor, which throws every highway open to the individual owner of the machine and does away with the immense advantage previously enjoyed by those who had acquired the monopoly of the comparatively few routes along which it is possible to lay down rails and operate trains. It is obvious that the motor, both as a passenger and freight carrier, is as yet only in its infancy; and when the flying machine comes, as eventually it will come, into general use the individualization of locomotion will be complete.

In short, the philosophy that bases its conclusions on the conditions that happen to prevail at any given moment in the machine industry is necessarily building on quicksand, since the machine itself is undergoing a veritable revolution along the individualistic lines we have indicated.

This delusion respecting machinery has led the Socialists into ridiculous assumptions on the subject of centralization in general, committing them for a couple of generations past to the pipe-dream that under the régime of Capitalism the middle class is doomed, by the natural development of the economic system, to speedy extinction. On the other hand, in proportion as the capitalistic system develops the numbers and influence of the middle class increase, until in America--the country in which Capitalism has attained its greatest growth--it is well nigh omnipotent.

[T]hose who have studied the works of such profound writers as Herbert Spencer, Buckle, Sir Henry Maine, and others too numerous to mention are well aware that the history taught the Socialists through Marx and Engels is partisan history, and that the real movement of humanity has been to get away from the military régime of authority to the domain of individual freedom. It is this movement with which we have allied ourselves, convinced that there is nothing too fine for man, and that it is only under conditions of freedom that man has the opportunity of being fine. The tendency must be toward a finer, which means a freer, more self-governing life.

My own hatred of State Socialism, in all its forms, springs from my conviction that it fosters in the Individual this terrible psychology of invasion; that it denies the existence of Rights which should be secure from assault; that it teaches the Individual that in himself he is of no account and that only as a member of the State has he any valid title to existence. That, as it seems to me, reduces him to helplessness, and it is the helplessness of the exploited that makes exploitation possible. From that flow, with inexorable logic, all wars, all tyrannies, all those despotic regulations and restrictions which to-day are robbing Life of all its elasticity, its virility, its proper sweetness. State Socialism is a military creed, forged centuries ago by conquerors who put the world in chains. It is as old as the hills, and, like the hills, is destined to crumble into dust. Throughout the crisis of the past eight years its failure as even a palliative policy has been colossal.

Conclusion

[O]ur suffering and danger do not come from Free Industrialism but from an Industrialism that is not free because it is enslaved by Monopoly and caught fast in the clutches of that invasive military machine--the State. Monopoly is the enemy, the most dangerous enemy the world has known; and never was it so dangerous as now, when the State has made itself well-nigh omnipotent, Monopoly is State-created, State-upheld, and could not exist were it not for the organized violence with which everywhere the State supports it. At the behest of State-protected Monopoly the ordinary man can be deprived at any moment of the opportunity of earning a livelihood, and thrown into the gutter. At the command of the State, acting always in the interests of Monopoly, he can be converted at any moment into food for powder. Show me, if you can, a tyranny more terrible than that!

I call myself an Anarchist because, as it appears to me, Anarchism is the only philosophy that grips firmly and voices unambiguously this central, vital truth. It is either a fallacy or a truth and Anarchism is either right or wrong. If Anarchism is right, it cannot compromise in any shape or form with the existing State régime without convicting itself thereby of dishonesty and infidelity to Truth. Tyranny is not a thing to be shored up or made endurable, but a disease to be recognized frankly as unendurable and purged out of the social system. Personally I am a foe to all schemes for bolstering up the present reign of violence, and I cannot regard the compulsions of Trade Unionism, Syndicalism, and similar States-within- States, as bridges from the old order to the new, and wombs in which the society of the future is being moulded. Such analogies seem to me ridiculous and fatally misleading. Freedom is not an embryo. Freedom is not a helpless infant struggling into birth. Freedom is the greatest force at our command; the one incomparable constructor capable of beating swords into ploughshares and converting this war-stricken desert of a world into a decent dwelling-place.

Anarchism rests on the conviction that human beings, if granted full and equal opportunity to satisfy their wants, could and would do it far more satisfactorily than can or will a master class. It is inconceivable to us that they could make such a failure of it as the master class has done. We do not believe that the peoples, having once become self-owning, would exhaust all the resources of science in murdering one another.

We are for abolishing Capitalism by giving all men free and equal access to capital in its strictest and most proper sense, viz., the chief thing, the means of producing wealth--that is, the well-being of themselves and the community... The work of their brains--these few who "scorned delights and lived laborious days"--has put into our hands a capacity to produce which is practically illimitable, and a power to distribute which laughs at physical obstacles and could, by the exercise of ordinary humanity and common sense, knit the entire world into one harmonious commonwealth and free it forever from the mean and sordid struggle that keeps it in the sewer. These few, knowing no God but Truth and no religion but loyalty to Truth, have made Nature, which was for ages Man's ruthless master, to-day his docile slave. In all history there is nothing to compare with the Industrial Revolution wrought by Science, but the harvest of that mighty sowing we have not as yet even begun to reap.

This is the dream; but it is not a dream. The abolition of human slavery is essentially the most practical of things. The adjustment of individual and social life to conditions that have been completely revolutionized by the advance of human knowledge is an adjustment that must be made.

FINIS

Just a thought.

Just KenCLASSical Liberalism